I am about to drape myself in academic regalia--a black gown and a hood adorned in white and Williams purple--to sweat through the better part of an outdoor ceremony in nearly 100 degrees of heat for the next two hours. The event, of course, is Choate's graduation exercises.

My good friend Chuck Timlin (note the obligatory Samuel Johnson reference) wrote the following piece, which appeared in the Hartford Courant a week ago--a reflection that perfectly captures my own feelings about the day.

"Great Joy Tempered By Deep Sadness"

A Sunday early in June is the most bittersweet day of each year for me. When I wake up that morning, I already know that I will go to bed that night emotionally wrung out. Each year, I experience the most selfless joy for my students as they graduate from Choate Rosemary Hall and the most selfish sadness for my loss.

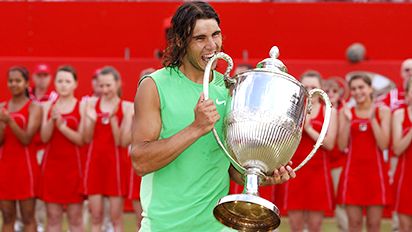

After sipping my morning coffee, I shave and shower and watch the beginning of the men's French Open tennis final (also always played on our graduation day) as I put on a pair of dress pants, shirt and tie. Then, I go down to the basement closet and look for my robe, red and white hood, and mortarboard. I am always a bit surprised to find them still there, as if even the inanimate world would refuse to participate in the wrenching ritual about to unfold.

At 10 o'clock, I walk across the street on campus and take my place in line with my colleagues. At 10:30 the bagpipers in the front unleash their stirring swells of Caledonian war music, and we begin our march through the gauntlet the senior class has formed. All the girls wear beautiful white dresses and hold single, long-stemmed, crimson roses. The boys wear dark suits with crimson roses pinned to their lapels. They no longer look like boys and girls but seem to have transformed overnight into men and women. As we saunter through, seniors cheer and call out greetings to their teacher friends. I begin to see eyes watering up. I think those haunting bagpipes and the physical fact of our marching strikes the first note to them that this is indeed the beginning of the end.

Once the teachers pass them, the students pair up and march behind us toward their seats, facing ours on either side of the stage. During the long ceremony, I have time to scan the vast sea of students and their families on the green lawn. The graduates seem to tingle with excitement and expectation. Why shouldn't they? All they can think about now is that high school and all of its restrictions upon them are ending.

I look more closely to find the students I have come to know more as friends than pupils. A girl with whom I read Hamlet shows none of the sweet prince's melancholy. A boy I coached in basketball bats playfully at one of the beach balls bouncing above the scene. They are in love with the moment. I am trying to hold onto the last minutes of a relationship that in a couple of hours will never be the same.

As the seniors line up for the awarding of diplomas, I try to pay attention to all of the names announced. I want to see every student to whom I've grown particularly close receive his or her diploma. But every year, as the Y's are being called out, I look over my roster of graduates' names and realize, disconcertingly, that I missed seeing several students walk across the stage. I feel as if I have betrayed them somehow.

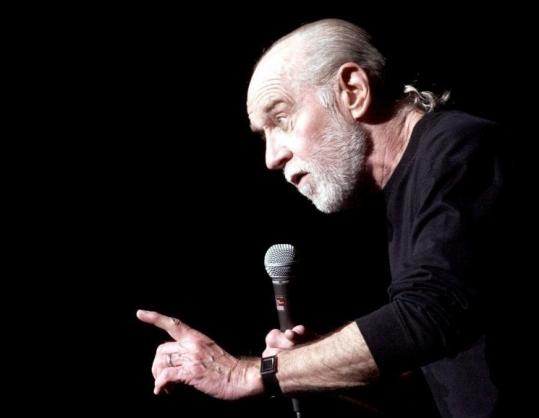

The ritual concluded, we teachers march back out between the rows of seats. The seniors, now graduates, again yell out our names, and more tears well up in eyes. Then it's onto the luncheon. For the next hour or so graduates and parents come up to us to offer thanks, little gifts, and requests for photos. A student gives me a parting hug and whispers, "I will never forget you." I have learned to quote Dr. Johnson's fine reply to his pupil Boswell on a similar occasion: "Nay sir, it is more likely you should forget me, than that I should forget you."

And then, they are all gone. Later that afternoon, I take a long, slow walk around the campus. It is a ritual that I must re-enact each year to confront my mixed emotions. I feel drained from the academic year just ended. And, having had so many heartstrings cut earlier that day, I feel the blues coming on.

There is a quiet about the campus that in a week will feel therapeutic but which now feels unreal. It's too quiet, as if all the life has been drained out of the place, turning it into a vacuum.

This is a crazy way of going through life. You get used to seeing these kids just about every day for three or four years, you have given a large part of your heart to them (and they have given even more of theirs to you) and then snip — the cord is cut and you may see some of them once or twice in the next 10 years.

They say that the three best reasons for teaching are June, July and August, but "they" don't know what it feels like to die so many little deaths at the crossroads of spring and summer.

In The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald's character Jordan Baker praises fall as the season when "life starts all over again." She was right. I know that only September's regeneration of the student body will make me feel whole again.

Well said, Chuck.